I keep flowers in front of my mother's picture on the windowsill in the office now ‑‑ behind my father's desk. I may not have to do this since I have begun writing ‑‑ but I have to water the tete‑a‑tetes before they die, or if they haven't already. The picture is a studio portrait, taken in the 30's, of a very beautiful woman in her late twenties; there is a cobalt cast in the darkest shadows ‑‑in her hair, in her nostrils, in her eyes. She has lovely shoulders, and she looks out of the photograph, facing left, her chin tilted up, as if she is looking over the heads of an adoring crowd. She is serene. I think I never ever saw her that way. In death she looked grim, as I suppose do all the dead when their skin settle closer to the bone, like a powerful and angry ancient empress, like a white version of a peat mummy. In front of this posed portrait, I keep a small candid color photo of her sitting in a chair, next to the bed in her apartment in the retirement center. She is facing right, chin on her palm, her elbow on the back of the chair ‑‑ still posing, but looking straight at me. She is a handsome old woman, with a hint of a smile, and wonderful white hair. I don't know when this picture was taken. Probably, she had already begun to lose her keys and burn the cookies. I have kept the tall glass from the 7 day memorial candle filled with flowers since the wax in it burned away. Flowers were among the things my mother loved most. Among my earliest memories is collecting Japanese beetles from her rose bushes when I was three. They tickled, but their iridescence dazzled me, and I think she was fascinated by them as well, even though we dropped them into a can to die. She taught us all the names of flowers, took us to the park on Saturdays in the spring to pick violet bouquets. She taught me and my sister to pick only one violet from each plant, so there were plenty to go to seed. She told us never to pick them all. "If everyone picked them all, there would be none left." not as wise now at it seemed then, but I was left with the idea. It was probably against park regulations to pick even violets, but she never cared much for rules if they contradicted her own reason and she thought she wouldn't get caught. She knew the names of flowers and of birds, and she told them to us, and now we know them. I anticipate that I will start to forget them. In her last ten years , she forgot them all. For some time after the obvious start of the decline, she struggled to describe a flower whose name escaped her, until she often came up with words that described it as if she were writing a popular botany text. Then I could name it for her, and she could forget the name. When circumlocution was beyond her, she settled for looking. She would gasp at a flower in stunned delight, as if she had never before seen such a thing. In effect, I expect, she hadn't. By that time her short term memory was so ruined that she had never seen a flower before ‑ at least she didn't remember having seen one. What's the difference? There was something awesome in these encounters ‑‑ watching her transfixed in front of an amaryllis ‑‑ discovering the world anew every day.

This isn't funny;

I've lost my sense of humor.

Her I am ‑ writing down my dreams ‑

and mother is the dreamer.

"mom," I say, "my dreams!" but

she rambles on,

speaking to the grandchild who has left the chair

and gone upstairs,

I can't make sense of it anymore;

I don't know how to answer.

We're in the kitchen with the flowered

wallpaper and the white rabbit

lopes along the floor;

she's dropping ashes in the soup,

laughing ‑ a woman, younger than I ‑

with gray braids and horn rimmed glasses

asking if I'll still sit on her lap when I am twenty ‑

Well, I won't:

I'll hold her hand;

explain where we're going;

button her buttons; say

goodbye mom. I'll be back next week.

In my dreams

the house is burning down.

This isn't funny. I'm surprised. I thought I wanted to understand what happened. I thought I wanted to learn what there was to know about this disease or process or whatever the hell it is that makes a person grow backwards and crazy and turn into a child. The machinations of the brain are fascinating, Why? why? and why?

I thought I wanted to write about my mom and how I grew to appreciate her spirit , how I resolved my growing up conflicts with her, how I stopped hating her; how I stopped being angry at her; how I stopped resenting her power over me, how by changing places, I realized how much I loved her. I thought I wanted to prove that this experience was not all "tragedy" (as she would say), how despite the obvious pain and suffering, I wanted to announce my gains, my discoveries so that others ‑ so many of you ‑ could look, in your ordeal, at the bright side, could explore the positive aspects of losing a parent ‑ could somehow find the parent who would inevitably, during this process, become your child.

Yes, there is some benefit to feeling like you're leaving your mother alone at her first day of school. Tears come to your eyes as you leave the room knowing that your precious child is alone and frightened and feeling betrayed because you have left her there. So I felt when I moved my mother from her apartment to the nursing floor. I sent her cats away and replaced them with stuffed toys. I got her a new TV to keep her company. I brought her comforter and her photographs to the new room. I brought the 10 foot dracaena that had been her mother's, that grew in our house on Carpenter Street and our house on Calvert Road, never attaining more than five feet and six leaves, that found the perfect exposure on the 22nd floor, flourished, and was forced to bend and grow along the ceiling. The Care Center room I brought it to was dim; the exposure indirect, the window looked to the apartment building across the street, which blocked the sun.

Mother didn't register all this information. She knew that things were changing. She had stopped resisting. An attendant asked her questions from a xeroxed intake sheet ‑ read her rights, and asked her to sign that she had been given all the information she needed ( “I understand that one of the complications of this procedure could be death, yes.”) and that she understood it. She didn't want to sign anything without her lawyer. She didn't want to sign until it had all been thoroughly explained. She didn't want to sign until she understood what the attendant was talking about ‑ which she didn't - and she wouldn't ‑ ever again. And beside the attendant was black, and my mother felt she was being ordered around. It went against what was left of her picture of a rational world.

When I said goodbye to her at the door of the elegant little living room adjoining this moderated nursing unit, I reassured her that she would adjust to the new room, that I would call her regularly, that I would come back in a week, that I would bring whatever she needed, and convinced her that she needn't come all the way down the elevator with me, ‑ I would be fine (sure I would!) . The unit door was still ajar and she was waving when the elevator doors closed. I was crying. I had left four children in kindergarten and had forgotten the feeling. Now I remembered not only my feeling, but my mother's as she left me in school on the first day. [actually it was Hazel, my nanny] You see, what I mean is, I integrated, I absorbed, I really learned. I was unseparating. We were coming back together. (I thought, until now, that was a positive. But I'm beginning to wonder.)

When I decided to write this, I thought I would focus on the charming incidents that showed my mother's bright side, the part of her that was paradoxically left when the light of reason dimmed. In her senility, she maintained an extraordinary social sense and an entertaining appreciation and good humor that was often overshadowed in her earlier rational self. In her dotage, she did not undress herself in the doorway of the nursing center and cry "I'm cold." She did not yell "nurse, nurse" for hours at a time. She did not look into her hands despairingly and ask whomever passed by to read the note she held that was not there. She had been miserable in her apartment, understanding little by little that she was falling apart. She was beside herself when we told her she would have to have a companion. She fought me when I explained that she could no longer stay in her apartment. But now, in the Care Center, she had outrun her misery.

When she was unhappy, (professionals would call it agitated), it was in response to being handled ‑ " Judy, we're just going to change your pants, now" ‑ she never responded well to being given orders, even those nicely worded. She had a nose for position; and, in real life, she was the one who gave the orders. She had some trouble with the other "inmates" which, rarely, gave rise to physical violence, ‑ the shaking of a fist, a side swipe, a skin tear ‑ incidents I was usually notified of. She was in the habit of traveling through the drawers and closets of all the rooms on the floor and redistributing the contents. When other residents, slightly more alert than she, recognized a territorial violation, they yelled at her. And she yelled back. As far as she was concerned, they didn't know what they were talking about. She maintained a certain superiority after a fight and even though she could be solicitous of others in the unit, she spoke a little cattily about them, as if they were her office rivals.

She was disturbed by dreams ‑ I'd call them that. There were times, early in her residency on the floor when she was haunted by a situation that existed only in her mind ‑ an argument unsettled, a body unfound. Once on a Sunday, she told me a man had died and they wouldn't let them see the body. ("They" I presumed were the nursing care staff, and " them," the residents.) According to her, the man had died three days before and she had been looking for the body ever since. I imagined her torment, looking for him since Thursday until I realized that the idea had probably arisen at the moment she told me about it. Now I imagine that the torment of a moment might equal the torment of three days. But then, I was relieved. As her dementia progressed and she became less coherent, she seemed incapable of constructing stories with enough integrity to hold her attention, and rambled on to an unseen someone or “someones” about things that did not appear painful.

Otherwise, she enjoyed walking and talking with aides and with me. She always complimented them on their beautiful skin and their hairdoes. She just loved them. She was happy to see me, throwing up her hands at intervals to say that she had just that moment realized I was there and how wonderful it was that I came, and did it take me long. I was her own dearest daughter even if she had forgotten the word. For the time I was with her, I was the most important person in her life.

And she loved Michael and his hat. She flirted with him as soon as she saw him. He treated her like a grand lady and she delighted in his attention: a coy old lady. For the first year after she met him, she always asked when we were getting married. Whenever he left the table at the restaurant where we took her, she asked me why he didn't want to marry me. She made suggestions and gave advice. (It appeared that marriage was the biggest light on her Christmas tree.) But she enjoyed going out. She marveled at the wonderful restaurant we had just discovered. (We went there every Sunday.) She charmed the waitresses. She made faces at the wine and then said it was the best she had ever tasted. She loved dessert. She expressed concerned about our comfort, worried about our long ride and told us to come only when it was convenient ‑ when we had no other plans.

So what am I talking about? Looking at the list I made to try to remember how things went. I don't remember how they went ‑ I thought I'd remember everything forever ‑ or until I got Alzheimer’s! The list is not a list of funny things. Their are entries that make me laugh. But most of them are not a bit funny. I'm losing my distance. I'm her daughter and I'm losing my distance. Where will that take us? A frightening thought.

In my wisdom, I also planned to learn about the science that fascinated me while my mother changed. The things I didn't know about the brain that explained why the lights went off and on, why so many Alzheimer’s and other senile patients share the same patterns, keep the same lights burning. I planned to read about pathology, talk to neurologists, simplify and describe what I learned so that it would illuminate the condition for others. Well, I met a protein, and I see that this will not be easy. So it's not funny, and it's not easy. And I think there isn't any answer. The Amyloid proteins are not any more instructive than Christmas lights. Reading about the physiological and biochemical bases of memory is like reading about the big bang theory. It does not answer the question why?

Ghosts I'm procrastinating. Finally at ten o'clock on Tuesday I called her. At that time, I called her every day. Often in the morning, but at other times as well. My mother never liked things to be too predictable. "If you knew what you were going to eat every Monday," she said, "it would be boring. I don't understand people who have a menu every week." They obviously lacked imagination. Besides, if I called her every day at the same time, it would be out of routine, not out of love and my true desire to talk to her. Mother didn't want her children to do things for her out of obligation. We should want to do what she wanted us to do, for ourselves ‑ and like it. At this point, I didn't mind calling her every day. I saw it as my responsibility. The conversation was necessarily limited, she repeated the same question every three minutes, and she couldn't relate to the things I told her about my life. If I talked about my job, she asked if I was getting paid enough, but I knew, by then, that the context of my life and anything new was beyond her understanding. I don't remember what we talked about really. But when I called I often could find out if something was going wrong, if her eyes hurt, or if she was angry at someone ‑ if Nathan or the nurse had not been in their office when she went down to get her medication; if she refused to wait and left without it and if the cat threw up. I called her. "Hi mom, it's Penny, how was your day?" "Hello, darling, are you at home. Did you work today? Are you tired?" "I'm fine. Did you talk to Naomi?" "I tried and tried to get her, but something was wrong with the phone. I was going to call you ‑ on my money for a change ‑ but the phone didn't work. Naomi did call me and Ceil called me to go down to dinner. I don't know why I can't get the phone to work properly." "Did you use the big buttons, Mom? Remember? We put the list on the wall beside the phone. You push one for me, two for Naomi, and three for Nikki." "Where is the list?" "I taped it up beside the phone. It's written in red pen. Can you see it? "Where is it? "Beside... the...telephone. On the right side of the telephone. Next to the cabinet. Taped on the wall. Look at the telephone. Turn your head toward the cabinet on the right. Do you see it?" "Oh I must have put it away where it can't get lost. I'll have to look for it. I only have to push one to get to you, really? Why can't I remember that? I'll work on it. " "Don't worry about it mom; it's not important. Wasn't it a beautiful day? Did you go for a walk today?" "I couldn't go out today, I have to straighten up here. I have to get the papers in order. I'll go out tomorrow." She had lowered her voice. "Mom. can you talk louder; I can't hear you." "No, I can't talk louder now. They'll hear me." "Who will hear you, mom. Is somebody there?" "I can't talk now. I have company>" "You have company. It's 10:15; who's there. Is Naomi there?" "No, not Naomi. I don't know them." "Mom, what do you mean? You just said you have company. It's kind of late. Who's visiting, somebody from the building?" Her voice was low and anxious. "There are four of them. I don't know them." "Where are they, mom? Are they in the kitchen with you?" "No they're in the other room. They're in the chairs." "Ok mom, can I say hello to one of them. I'd just like to say hello, ok?" "I can't ." "What?" "I can't. I can't talk to them. They don't talk." "Mom, I have to tell the kids something. I'll call you back." "Don't have to call back if you're too busy." "No, it's ok, I just have to do something now. I'll call back." I tried to work out the picture. Strangers are sitting silently in the rose velvet arm chair, on the sofa covered with the white plastic tablecloth and in the matching dining room chairs. For a moment, I thought someone might have broken in. The senior residence was a mark for petty criminals who counted on the confusion of the residents when they lifted and replaced keys, took small articles, copied down credit card numbers. When a resident missed something, there was always the chance that they had hidden it themselves, or had lost it themselves. The vision of an old woman alone confronted by 4 mute kidnappers? gangsters? was frightening because it was unreal. They didn't talk. My mother's karma held no gangsters. It wasn't real. I called the nurse on duty and asked her to visit my mom's apartment and see if she had visitors. The nurse called me ten minutes later to tell me that there was no one in the apartment but my mother and the cats. She had the TV on in the living room. Maybe the movements on the TV made her think there were people in there, she said. "Does she think there are people in there now?," I asked "Judy, do you have any company?" the nurse asked. "Yeah," my mother answered. "You!" My mother came to the phone, and I asked her about the previous visitors. She said that they went away, that the nurse was very nice." "G'night mom, I'll talk to you tomorrow. Go to bed ok?" "Goodnight darling. You rest too." The next day they were back. But they seemed less ominous. Perhaps by the second day, she knew them. They irritated her over the next few days by coming whenever they pleased. They morphed into a mother and father with children. The parents left the children with my mother and she was forced to take care of them, not knowing when the parents would return. She was very annoyed with these people . They were taking advantage of her kindness and hospitality. They didn't even tell her when they were going to leave the children, and the children were spoiled and ill mannered. She couldn't get anything done in the apartment and she didn't want to go out and leave the children alone. They had no names. She didn't have conversations with the parents. She must have felt able to talk to the children. Her long years of teaching gave her the authority to talk to any child, even one only she could see. She grew increasingly frustrated.

As I add to this section, I realize that my observations about my mother are really as much reflections of me and how I saw her as they are of who she was. Like anyone else, she wasn’t perfect, but she had a life before Alzheimers.

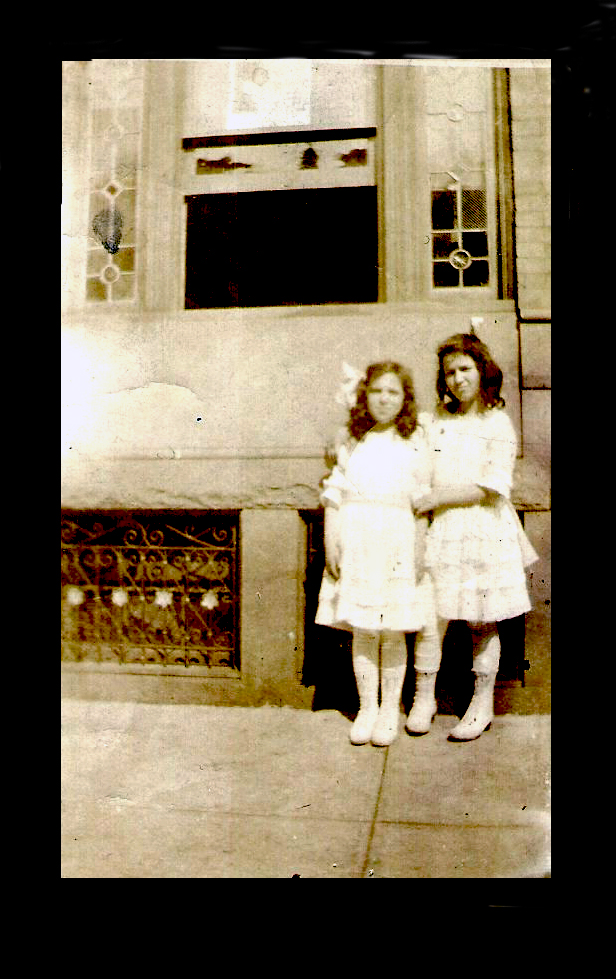

She was the fourth of 5 sisters who remained exceedingly close all their lives. She came from Poland to this country when she was eight years old, entered 1st grade and quickly got skipped to the third. She learned unaccented English and later tutored students with accents to speak English without a foreign accent. One of these was my father.

Her teachers appreciated her quickness and she loved her teachers. She decided that teaching was to be her career very early on, and with the help of her mother and older sisters, she maintained an academic curriculum, graduated from normal school and got a masters’ degree at Penn State. (There was subterfuge involved, as her father wanted her to take commercial courses and become a secretary.)

She always said nobody would guess that she was a teacher. She was wrong. She was always teaching. Often successfully, but sometimes to the dismay of her would be students.

She did teach all her life in inner-city schools with special education students. She became vice principal, worked with parents, cared for children and enjoyed her status. She was proud of herself and expected respect.

She was a good listener. All my cousins remind me of how comfortable they were talking to her about things they didn’t think they could talk about with their parents.

In later years, she was friend and guide for many of the younger women in her neighborhood, and ultimately was adopted into the motherless family next door.

She taught me how to look at nature, to not pick all the flowers, to identify birds. She could be manipulative and overstep, but she could be very kind. When she babysat two of my children and the dog, and after taking the children on a jaunt came back to find the dog outside the house and the inside wrecked, she said “poor dog.” She saw me through crises and did not judge me. She was brave.

As a senile old lady, she was “cute as a button.” She remembered the most flattering thing to say to strangers. She charmed caregivers and waiters. When I was in the elevator with her and other residents of her community, she would tell everyone that she couldn’t introduce me because “she didn’t remember her own name.”

She volunteered at the children’s center and helped them make book marks in the shape of worms.

In later stages of dementia, I would take her for car trips and we would have long conversations that no listener could follow. They were all about cadence and tone of voice, and we got along better than we ever did when we were both young. She was always looking at things for the first time. She had never seen such beautiful flowers, such beautiful children, tasted something so wonderful (or sour) as the wine at the restaurant, seen someone with such lovely skin (her caregiver).

I suppose that is what made me want to write about her last years. Despite her loss, I felt like I learned to appreciate her, to recover her in a way. I also learned about the joys as well as the sadnesses of losing your mind.